Immigrant dream plays out through son

Harvard's do-it-all star learned the game from his father and a host of NBA legends

O'Neil By Dana O'Neil

ESPN.com

The perfect form on his jumper? Larry Bird deserves credit for that.

The power end-to-end drive with a dunk to finish? Vintage Dr. J.

The sweet dribble penetration and kickout? Score one for Magic.

As Jeremy Lin dissected and bisected Connecticut to the tune of 30 points Sunday afternoon, his father sat in front of a computer screen on the other side of the country, watching his videotape library of NBA greats come to life in the form of his son.

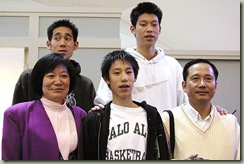

All those years Gie-Ming Lin spent rewinding his tapes so he could teach himself how to play a game he never even saw until he was an adult? All those hours spent in the local Y with his boys, schooling them in fundamentals over and over, building muscle memory without even knowing what the term meant? That silly dream, the one in which his children would fall in love with basketball as much as he had?

There it was, borne out in a gym in Storrs, Conn.

"Every time he did something good, they'd play it over and over again," Gie-Ming said from his home in Palo Alto, Calif. "I kept watching, and they kept showing him."

Soon the rest of the college basketball world might be turning its collective eye toward Jeremy Lin. Think about what the senior has done just this week for Harvard, which is off to its best start (7-2) in 25 years.

In keeping his team in the game right to the end, Lin scored a career-high 30 points and grabbed 9 boards in a 79-73 loss to No. 12 UConn. Then, in the Crimson's 74-67 upset at Boston College on Wednesday -- the second straight season Harvard has beaten BC -- Lin contributed 25 points.

He boasts an all-around repertoire rarely on display. Last season Lin was the only player in the nation to rank among the top 10 players in his conference in points, rebounds, assists, steals, blocks, field goal percentage, free throw percentage and 3-point percentage.

This year? He is merely second in the Ivy League in scoring (18.6 points), 10th in rebounding (5.3), fifth in field goal percentage (51.6 percent), third in assists (4.6), second in steals (2.4), sixth in blocked shots (1.2) and top of the pile in turning the heads of esteemed basketball minds, including Hall of Famer Jim Calhoun.

"I've seen a lot of teams come through here, and he could play for any of them," the longtime UConn coach said of Lin. "He's got great, great composure on the court. He knows how to play."

And he learned how to play thanks to his father's determination.

Jeremy is not the product of some Marv Marinovich in high-tops, desperate to cultivate the perfect basketball player, but rather a 5-foot-6 immigrant who long ago fell in love with a game and realized that in that game, his own children could gain entry into mainstream America.

Gie-Ming Lin was born in Taiwan, where academics were stressed and athletics ignored. He caught an occasional glimpse of basketball and, for reasons he can't explain, was immediately smitten with the game.

He dreamed of coming to the United States for two reasons: to complete his Ph.D. and "to watch the NBA."

That happened in 1977 when Gie-Ming enrolled at Purdue University for his doctorate in computer engineering. He flipped on the television, and there it was: the NBA in all its late-1970s glory. Kareem, Moses and Dr. J, with Jordan, Bird and Magic waiting in the wings.

"My dad," Jeremy said, "is a complete basketball junkie."

"I thought it would be great to play basketball," Gie-Ming said.

Only problem? He didn't have the slightest idea how. He had never picked up a ball in his life.

So he turned his attention back to those gripping NBA games. Armed with videotapes of his favorite players, Gie-Ming studied the game with the same fervor he studied for his Ph.D.

"I would just imitate them over and over; I got my hook shot from Kareem," Gie-Ming said, laughing.

It took him years to feel comfortable enough to play in a pickup game, and as he bided his time he decided then -- long before he even had children -- that his own kids would grow up knowing the game from an early age.

When first-born Joshua turned 5, Gie-Ming carted him to the local Y to begin teaching him those valuable skills stored on his videotapes.

Jeremy followed, and then youngest brother Joseph joined in what became a three-nights-a-week routine. The boys would finish their homework and around 8:30 head to the Y with their father for 90 minutes of drills or mini-games.

Forget that all of the players on those videos had long since retired, that the guy with Kareem's hook shot wouldn't hit Abdul-Jabbar's armpit. Gie-Ming recognized what so many other youth coaches have forgotten over time: The foundation for success is the basics.

"I realized if I brought them from a young age it would be like second nature for them," Gie-Ming said. "If they had the fundamentals, the rest would be easy."

Joshua would star at Henry M. Gunn High School. Jeremy would enroll at rival Palo Alto High, where Joseph is now a senior.

Jeremy was special. He had his father's passion, his own inner motivation and a frame that would sprout to 6-foot-3. A good enough scorer to play 2-guard, Jeremy also was a savvy enough playmaker -- thanks to his dad and Magic -- to play the point. He's a solid outside shooter, but his dad, Julius and Kareem conspired to give him a reliable game around the rim.

In other words, he was otherworldly, a kid so talented that his freshman coach stood up at the team banquet and declared, "Jeremy has a better skill set than anyone I've ever seen at his age."

Named to the varsity as a freshman, Jeremy would earn honors as sophomore of the year and two-time most valuable player in his league.

Immersed in the game as he was, Jeremy never thought he was anything but a normal kid who liked basketball.

Until, that is, the insults came at him, the taunts to go back to China or open his eyes.

He was an Asian-American basketball player, an oddity and a curiosity in the cruel world of high school, where nothing is safer than being like everyone else.

"It was definitely a lot tougher for me growing up," he said. "There was just an overall lack of respect. People didn't think I could play."

His father offered sage advice.

"I told him people are going to say things to him, but he had to stay calm and not get excited by these words; they are only words," Gie-Ming said. "I told him to just win the game for your school and people will respect you."

Once more, Gie-Ming was right. In his senior season Jeremy averaged 15 points, 7 assists, 6 rebounds and 5 steals, leading Palo Alto to a 32-1 record and a stunning 51-47 victory over nationally ranked Mater Dei in the CIF Division II state championship game.

Along the way, he converted some of the people who had mocked him. When Palo Alto played Mater Dei, students from both Jeremy's high school and rival Henry M. Gunn High crowded a local pizza joint to cheer for Jeremy and his team.

Converting people outside Northern California was more difficult. By his senior season, Lin was the runaway choice for player of the year by virtually every California publication. Yet he didn't receive a single Division I scholarship offer.

Lin doesn't know why, but believes his ethnicity played a part.

Asian-Americans make up just 0.4 percent of Division I basketball rosters, according to the latest NCAA numbers. That equates to 20 players out of 5,051.

Harvard offered an education with a hefty price tag. (The Ivy League offers no athletic scholarships.) But it also offered the chance to play Division I ball. So Lin went without hesitation.

Four extremely successful years into his college career, he now finds himself packaged into an uncomfortable box. Lin is at once proud and frustrated with his place as the flag-bearer for Asian-American basketball players.

The Harvard uniform, the Asian background, it all still makes Jeremy something of a novelty. What he longs for most of all is to be a basketball player.

Not an Asian-American basketball player, just a basketball player.

"Jeremy has been one of the better players in the country for a while now," said Harvard coach Tommy Amaker, who, as a Duke graduate and former head coach at both Seton Hall and Michigan, knows a thing or two about talent. "He's as consistent as anyone in the game. People who haven't seen him are wowed by what they see, but we aren't. What you see is who he is."

But stereotypes die hard and remain propagated by the ignorant. At UConn, as Jeremy stepped to the free throw line for the first time, one disgraceful student chanted, "Won-ton soup."

"I do get tired of it; I just want to play," Lin said. "But I've also come to accept it and embrace it. If I help other kids, than it's worth it."

In their 109-year history, the Crimson have never won an Ivy League title and have managed only three second-place finishes. They have had just one league player of the year -- Joe Carrabino in 1984.

The last Harvard man to suit up in the NBA? Ed Smith in 1953.

Lin could change all of that, a thought that boggles the mind of the man who fell in love with a sport so many years ago.

"All this time he was growing up, I never thought about Jeremy playing in college or professionally," Gie-Ming said. "I just enjoyed watching him play. I'm just so proud of him and so happy for him. I told him my dream already has come true."

Dana O'Neil covers college basketball for ESPN.com and can be reached at espnoneil@live.com

http://sports.espn.go.com/ncb/columns/story?columnist=oneil_dana&id=4730385